HIDDEN VALES

The Art of Music

A ‘vale’, in the literal sense of Bob Brown’s poem Hidden Vale, is a valley as elegantly portrayed by Sarah Stewart’s painting that graces the sheet music and the same-titled CD’s accompanying booklet. But ‘vale’ can also mean a world, our mortal, earthly life. Both meanings came to me when choosing this poem as the title piece for the CD, putting myself in a frame of mind to improvise musical sketches that might express the meaning of each of the 10 poems selected from Bob’s collection In Balfour Street (NewPrint, 2010).

Vale’s homophone, ‘veil’, is something that covers, protects and/or conceals - often a face from the elements or from scrutiny. But a veil can also be less tangible. Bob’s poems are both - they reveal a physical location (e.g., On Cradle Mountain) as well as gently mask, the better to see them, the emotional dramas. Bob’s poems often express the interplay between people and nature, in this case two tragic snowstorm deaths illuminating loss and love as well as the almost inhuman physical (.. ever nearer never..) effort of carrying someone through a blizzard to save lives.

The piano can be a physical and metaphorical veil that offers distance between the music, performer, context and audience; perhaps the better to hear it. My love of the piano goes back to when I was about 3 years old when I was given a toy red one-octave “grand” as a Christmas present, on which I tapped out the notes of the music heard while I sat in on my sisters’ dance classes. That trick saw me attend a nearby convent for music lessons where, in my early teens in the 1960s, my nun teacher (who climbed out the convent window at night to go to symphony concerts) taught me music has no value unless it is heard. Her wimple did not veil her spirit.

THE MUSES

That music acquires value when heard is part of tradition in all civilisations. In Ancient Greece, “mousike” meant the arts of the Muses - the Goddesses of music, poetry, art and dance. These performance synergies still exist. Australian poet Sarah Holland-Batt, commenting on e.e.cumming’s anyone lived in a pretty how town, hears and speaks it as “a beautiful piece of music-making”. Learning this poem by heart opened up her understanding of how “poetry’s meaning can be carried along and buoyed by its sound” (Poet’s Voice, WA Review, 29-30 August 2020, p18); perhaps best illustrated on the Hidden Vale CD by the track The Oddity (seagulls as … flapping wing things…). Holland-Batt’s award-winning first volume of poetry, fittingly titled Aria (2008), is described as ‘like piano music heard through a high window…’, demanding attention with a touch of magic where, as in Bob’s life, something is always about to happen.

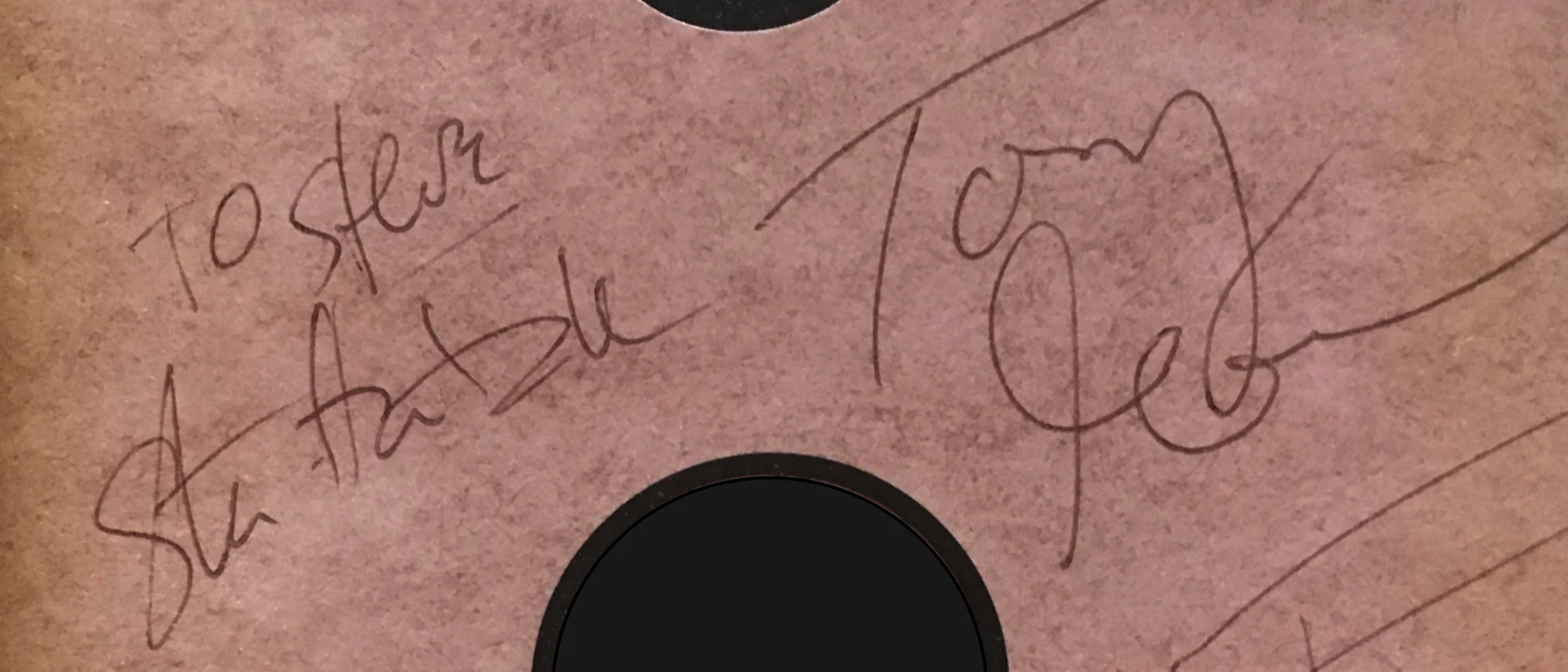

Such concepts also resonate with Sylvia Plath’s nature-based (rural Massachusetts, Yorkshire moors) depictions of the human and physical, abstract and concrete, states of mind and experience. For Bob, walking through Scotland in 1970, in a cursory glance he saw all that I’ll ever know. Such was his sense of wonder on climbing snow-covered Ben More he asked himself (and us, as readers) Why then ten score or so? Incidentally, Plath called her poet partner, Ted Hughes, a singer story-teller with a matching voice to perform. It is Bob Brown’s voice that perhaps drew most of the attention to our 2018 Winter Night at Liffey CD, his baritone expressing the emotional force of the poems, whether whimsy, delight or uncertainty (Winter Night At Liffey, available from bobbrown.org.au and the accompanying sheet music from stevecrumpmusic.com).

Across the centuries, the muses came together in delightfully different ways. For example, many of James Whistler’s paintings emerged from his imagination as if a form of music, most famously Symphony in White #1: The White Girl, just one of his music titles expressing internal and external harmonic structures. Other paintings that married music, art and the natural world include Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge and Symphony in Grey and Green: The Ocean. The evocative etching The Music Room is at first glance a family portrait; yet there’s an artistic veil here, giving the work varying foci between the expectation of the title and what we (at first) see.

SONG LINES

In The Odyssey (Book VIII), the audience / reader is told events happen not so much for contemporary reaction but “to make songs for far-off descendants”. Created around 3,000 years ago, yet post-modern in both its non-linear structure and featuring active roles by women and slaves, The Odyssey was initially passed down by poet singers; that is, it was (necessarily) composed to be heard rather than read. As such it was and remains a powerful exemplar of the oral tradition connecting peoples to their cultures from one generation to the next.

This is what the Song Lines of Indigenous Australians have done for tens of thousands of years, well before and beyond Ancient Rome, Greece, Egypt, or India. These song lines flow throughout Australia defining and detailing country and spirit, travelling in time and space much further than Odysseus. In 2015, I was gifted the privilege of standing at the most northerly point of the song line for Balang’s mob in the Northern Territory - closing one eye to concentrate on the significance of place, wisely keeping the other on the crocs.

When I first picked up Bob’s poetry book, In Balfour Street, I felt straight away they were song-like stories of his life few of us guessed at behind his well recognised enviro-political identity. Bob’s ‘odyssey’ has always been visibly personal: his tangible integrity, unflappable demeanour, not-for-sale convictions, and gracious good-humour that drew many of us into his orbit, even from a distance, and kept us spinning around him, his gravity pulling us towards things many of us still aren’t game or strong enough to feel or do on our own.

Thus, for me, Bob’s poems are not only of interest and value for contemporary audiences but also for future generations … vaguely touching / glimpsing each other’s lives… as is the case for Bob’s environmental legacy. The latter is epitomised by the Tasmanian South-West Wilderness and his old farm house at Liffey, northern Tasmania, which set the foundation for Bush Heritage Australia. When Bob paddled in a raindrop in 1972 he was fighting to save the original and world-heritage significant Lake Pedder from being dammed, but also fighting intellectually with what this meant for our planet and those yet to inhabit it… a press of knowing nothing pressed (..) clarity confusified.

DECORATIVE LEITMOTIF

When I set out to try to compose music for the 10 poems from In Balfour Street we hadn’t got to on the Winter Night At Liffey CD, I tried to do simple but atmospheric musical motifs that would infuse a recurrent sound associated with Bob’s poetic themes. I heard my music sitting further back in the mix than the quite formally shaped melodies I had conceived for the four earlier poems recorded on the Winter Night At Liffey CD. Also, I was attracted to the concept of ‘continuous music’ associated with Lubomyr Melnyk, as it encourages the pianist to respond variously to a music score rather than play ‘note perfect’ from start to end as if in an examination. For the Hidden Vale CD, ‘continuous music’ seemed a fitting strategy for the melody to be quite flexible around the spoken word which can easily, and interestingly, change (timing, words, delivery) every time the piece is performed.

I thus set out quite consciously to shape the musical motifs for these 10 poems around a shared, simple chord structure, mainly C major 7, D minor, G major, with variations, to give them a harmonic unity and allow for easy transitions to improvisation, even experimentation, in any subsequent performance. This worked quite well for a while. For example, few might gauge on first listening that My Godfriend, Hidden Vale, and Oddity have pretty much the same chord sequence, so different are their moods and execution.

Yet, for all 10, this chord pattern proved a little too consistent so I replaced what I had for Considering Life and went to a totally different, much loved but under-used, chord sequence employing sharps to give a higher pitch by one semitone, improvising almost to the note what you hear on the CD and can play from this folio. I outline that development in a blog on stevecrumpmusic.com.

I turned to E flat / A flat major for Thoughts While Staring At the Sky to get that dreamy effect, and F major / B flat major for The Birds, and On Cradle Mountain to introduce a more solemn, reflective mood. A good friend, Pete Costello, who trained as a violinist at the Tasmanian Conservatorium of Music, was the first person apart from Bob and Paul to hear all my rough demos for this CD and kindly observed.

I hear them as romanticism meeting haiku. Of course ‘haiku’ is a three line poetry form but all your pieces seem to be able to deliver their message in a concise way, unlike the romantics, and I consider this a strength indeed - a modern romanticism.

This is way too kind, but captures the intent of what you hear on the CD and play from this folio. You can hear and see Pete on fiddle on a clip of the recording of Tarkine Sunset (takayna) if you scroll down on stevecrumpmusic.com/news - below which is the full melody used as the soundtrack under a collage of Bob’s photos on a video for the Bob Brown Foundation end-of-year message in 2017. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that Tarkine Sunset (takayna) is one of the most downloaded of my songs by community radio in Australia.

CLOSER TO TRUTH

Monique reminds me of Bob in so many ways, though I didn’t know this ’til I met her in person, just a few months ago. Her ARIA awards and nominations only hint at Monique’s unlimited talent, depth of humanity, instinctive musicality, lyrical insights and unguarded warmth. Now a veteran of a harsh and unforgiving industry, Monique is being honoured in 2020/21 with a retrospective of her work in collaboration with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra.

From her breakthrough Fool For You and The Change In Me (featured on her debut album Thylacine), through soundtracks on television productions like The Secret Life of Us, collaborations with musicians of the stature or Paul Kelly, to her new work poignantly on display in Poland and the TSO collaboration Closer To The Truth, Monique personifies the consummate professional musician. This includes her commitment to assisting Indigenous women’s leadership in music, facilitating all aspects of music programs for young people with chronic illness, and guiding emerging song-writers.

A gum leaf adorns Monique’s favourite 1998 acoustic Maton guitar, a statement of the synergy she feels with the flora and fauna of Australia proudly on show on stage and in the naming of her Thylacine House Studio in Hobart. The depth of Monique’s musical instincts and skills was on display in the first few minutes I sat down in her studio in front a Nord synthesiser. Monique suggested I play one of the pieces I had written for Bob’s poems so I chose The Birds thinking I couldn’t possibly get four chords wrong (though at first I did). Monique started reading the poem (the first time she’d seen it) then seamlessly segued into a vocalisation that immediately was perfectly attuned to the mood of the poem.

The final version of The Birds kicks off the CD, spine-tingles triggered by her sung ‘outro’ after Bob’s fine reading. Monique inhabits the song, inhaling Bob’s reading and my piano to exhale a vocal that sets the scene for other tracks: On Cradle Mountain, Considering Life, Oddity and Along The Road.

CONTRIBUTED ARTWORK

In the booklet that’s part of the packaging for the Hidden Vale CD, and in these pages, the musical sketches plus ambient vocals around Bob’s readings come together with the art of Val Whatley, Jon Kudelka, Margaret Murray and Sarah Stewart, the artistic photography of Tabatha Badger and artistic design of Mic Rees - multi-generational intersections of their muse with Bob’s written and spoken words. Val spent her lifetime with brush and easel in the Tasmanian wilderness and her flower garden, one of the lucky few to have seen first-hand, and painted from the beach itself, the original Lake Pedder. Jon is known for his whimsical, gently satirical cartoons, mirroring Bob’s modus operandi that, whilst triggering a smile and perhaps / hopefully self-realisation in the reader, pack such a powerful punch that Jon has won political cartoonist of the year twice, on top of two Walkley awards.

After graduating from the National Art School, Margaret was commissioned to paint a series that captured the beauty of Lord Howe Island and, thirty years later, she’s still there. Her studio sits atop a rise where she captures in line drawings the local birdlife in fine detail, birds that are part of the reason for heritage listing of LHI. Looking for an outlet for her creativity during Covid-19 restrictions early in 2020, Sarah took up her brush and paintings just flowed from her hands, one artwork perfectly expressing Bob’s ‘hidden vale’.

Tabatha has an intrinsic love affair and deep fascination with the natural world, expressing the true meaning of ‘intrinsic’ - belonging to something by its very nature. Tabatha sees her photographs as a glimpse of a ‘memorable illuminating moment’ she not only captures on film for us but also offers as profound insights into the value and magnificence of that natural world. Unsurprisingly then, Tabatha is a young very active voice in local (Freycinet National Park) and state (Restore Lake Pedder) conservation issues as well as running the best coffee ‘wanderlust’ van (Hazards Brewing Coffee Co.) in Tassie.

Mic’s design work for the Hidden Vale CD, sheet music and poster draws on his artistic sensibilities, recognised by a residency at Design Tasmania where he explored the possibilities of art on an iPad. One of those paintings graces the cover of my first CD, “Midnight Rain”, done in the middle of the night during a raging storm flowing through Launceston Gorge. Mic’s work has been published nationally and internationally, drawing praise for the interplay of traditional onsite process with experimental / digital execution.

FOLKTALES

At my stage of life I never thought I’d find myself doing the housework listening to Taylor Swift (hugely talented and mindblowingly successful yet, until a few months ago, typecast as mainly appealing to teenagers). I’m happy to be wrong (again!), though my excuse is I hear a lot of nods to Joni Mitchell in Swift’s Folklore, a CV-19 isolation release. While Folklore doesn’t have anything musical that knocks me off my perch (though lots of nice piano!) there is so much integrity and completeness to the 16 tracks it reminds me of Bob’s “In Balfour Street” poetry collection and Monique’s 25-year-oeuvre. Taylor Swift’s choice of title was deliberate - the prologue in her lyrics booklet observing,

A tale that becomes folklore is one that is passed down and whispered around. Sometimes even sung about (…) Someone’s secrets written in the sky for all to behold.

So behold Bob’s poems, play these haiku-like but not immutable musical sketches, sing along as if Monique, delve deep into the experiences, landscapes, mindsets, assertion of the over-riding beauty of people, this planet, of life waiting to be found in Bob’s words and readings. I hope doing the housework, bushwalking, at work, wherever and whenever, you’ll burst out with some of Bob’s phrases: an emphatic Exactly!, an affectionate, How Good!, a heartbroken Why?, a hopeful If only, passing on the whispers of Bob’s heart.

SC Spring 2020